This article was written for the February 2018 edition of Executive Magazine.

At the end of January, Lebanon signed its first exploration & production agreements (EPA) with a consortium of companies composed of France’s Total (as operator), Italy’s Eni, and Russia’s Novatek. The consortium had placed two separate bids on October 12, 2017, the only ones received in Lebanon’s first offshore licensing round, for Block 4 and Block 9. With the contracts signed, Lebanon can now look forward to the exploration phase. The consortium has committed to drill two wells in 2019, one in each block. But what can Lebanon expect prior to drilling?

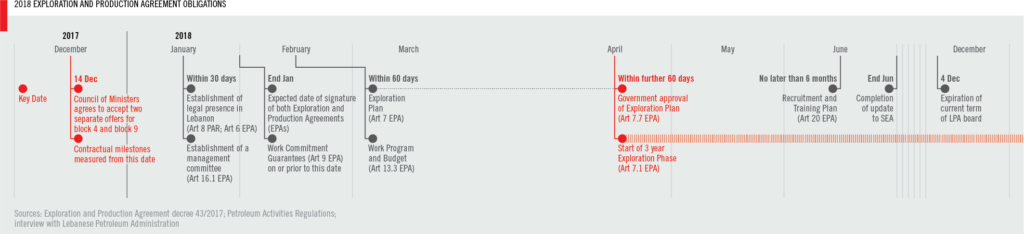

The Council of Ministers approved the award of exclusive petroleum licenses for exploration and production to the consortium in these two blocks in a cabinet meeting on December 14, 2017. This is what the EPA—the contract between the State and the consortium—refers to as the “effective date,” and our starting point to map out the road ahead in 2018.

The timeline is divided into two parts. The first, and larger, part focuses on companies’ obligations arising from their exploration and production licenses, the second sketches out the Lebanese state’s petroleum program in 2018.

By now, the three companies forming the consortium should have established a legal presence in Lebanon, staffed and able to carry out its rights and duties. In addition, they should have established a management committee to authorize and supervise petroleum activities. Each one of the companies has the right to appoint at least one representative in this committee. Lebanon may also be represented in this committee: The energy minister and the Lebanese Petroleum Administration (LPA) are entitled to appoint representatives, though these will only have an observer status.

The exploration phase will extend over a maximum period of six years, divided into a first period of three years, and a second period of two years, which may be extended for an additional year. The consortium is expected to submit the initial exploration plan to the energy minister and the LPA within 60 days of December 14, 2017 (the Effective Date). The plan should be approved within a maximum period of 60 days, if it meets all the criteria specified in the EPA. On the day it is approved, the exploration phase will have officially started.

Prior to the signature date, the companies must have provided work commitment guarantees to safeguard the state in case of failure to fulfill the minimum work commitment specified in the EPA. These are the tasks that the consortium is required to perform (excluding an event of Force Majeure). In the first exploration period, which starts on the date the Exploration Plan submitted by the Consortium is approved and extends over a period of three years, these tasks include conducting surveys, if it is deemed that existing surveys are not enough, and drilling exploration wells, starting in 2019 in Block 4 and in Block 9.

Within 60 days of the effective date, the companies must prepare a detailed work program and a budget for exploration activities, consistent with the requirements of the exploration plan, and submit it to the LPA. The regulatory body will either approve the work program and budget within a maximum period of 30 days, or reject it, in which case the decision must be explained to the companies in writing so that the companies may submit a revised version.

The exploration and production agreements between the consortium and the State include local content clauses designed to encourage the Lebanese economy. Among these is a requirement to give preference to Lebanese goods and services in awarding contracts, even if the local company makes offer up to 5 percent (goods) or 10 percent (services) more expensive.

Companies are also required to recruit 80 percent of their workforce from among Lebanese nationals. As this is hard to achieve at the beginning of their activities, the legislation allows a certain flexibility. Companies are expected to devise a detailed recruitment and training program. A proposal must be submitted to the LPA within six months after the EPA’s approval. An updated program for recruitment and training will have to be submitted to the LPA by December 31 of each year. If companies at first cannot meet the 80 percent threshold, they will be required to submit a written explanation on their own behalf, and on the behalf of their contractors, detailing the reasons and requesting an exemption. In addition, companies are also expected to assign a budget for training public sector personnel working on the oil and gas sector, starting with $300,000 per year, with a 5 percent increase each year, until the beginning of the production phase, at which point the amount will increase even further. These costs are recoverable costs for the companies.

For the Lebanese state, 2018 will be equally busy. Parliament will be busy discussing new oil and gas legislation, including an onshore petroleum resources law and a law codifying transparency measures for petroleum activities. These two pieces of legislation have a reasonable chance of being passed this year. Two other draft laws are expected to draw intense debate in and outside Parliament this year: A law to establish a national oil company—although Article 6 of the 2010 Offshore Petroleum Resources Law provides for the establishment of a national oil company only “when necessary and after promising commercial opportunities have been verified” and indicates that the company would be established by the Council of Ministers—and a law to establish a sovereign wealth fund, in addition to establishing a General Directorate for Petroleum Assets within the Ministry of Finance. In both instances, and as anyone would expect, the limits of the debate will not be confined to sectorial considerations and likely open to political meddling.

In addition, Lebanon is planning to update the 2012 Strategic Environmental Assessment, an environmental policy planning tool to guide decision making and predict how the environment is expected to change under different scenarios. A new version should be completed by end of Q2 2018.

In 2018, as in 2017, power generation is going to be among the government’s biggest concerns. Lebanon’s various political factions do not see eye to eye on this front, and progress has been painfully slow. Plans to acquire floating storage regasification units (FSRUs) and to import liquified natural gas for power generation, a project that has been repeatedly postponed since 2013, could be reactivated this year. Two tenders, one for the regasification units and another one for gas imports, are currently being studied, but there are no indications as to when exactly they will be launched.

A big question on everybody’s mind this year is the maritime border dispute between Lebanon and Israel. Despite the heated rhetoric at times, the area has been stable for over a decade. Is the US planning to resume mediation efforts? Is the United Nations considering a contribution on this front? Awarding Block 9, which includes an area that is claimed by Israel, is once again raising attention to this subject.

Another critical milestone this year is the expiry of the LPA board’s mandate in December 2018. The current board was appointed in 2012 for a period of six years, renewable once. It is not clear at this point if their mandate is going to be renewed or not. If it is not, it remains unclear how the next board will be selected. When the current members were appointed in 2012, it was reported that they had been selected according to a procedure valid once, suggesting that the appointment of the next board might not follow the same procedure. These are questions that should be clarified reasonably well in advance, because, whether the mandate will ultimately be renewed, or whether a new board will be appointed, these are political decisions, and as we have warned before, every step of the process requiring a political decision is a potential obstacle. More importantly, there are EPA obligations this year (see the timeline) and beyond that require LPA participation or oversight. Better to anticipate than defer.

On a side note, and if Lebanon wants to send a positive and symbolic signal early in the year, a good starting point would be to publish the two contracts that were signed at the end of January with the Total-Eni-Novatek consortium. Failure to publish the contracts would undermine efforts to build a clean and transparent Lebanese oil and gas industry.

Pingback: Liban: Trois conférences pour répondre aux urgences - Middle East Strategic Perspectives

Pingback: The maritime border dispute between Lebanon and Israel explained - Middle East Strategic Perspectives